Western Entanglement

Two new memoirs illustrate the expanse and variability of conflict, as well as the infinite variety of human experience.

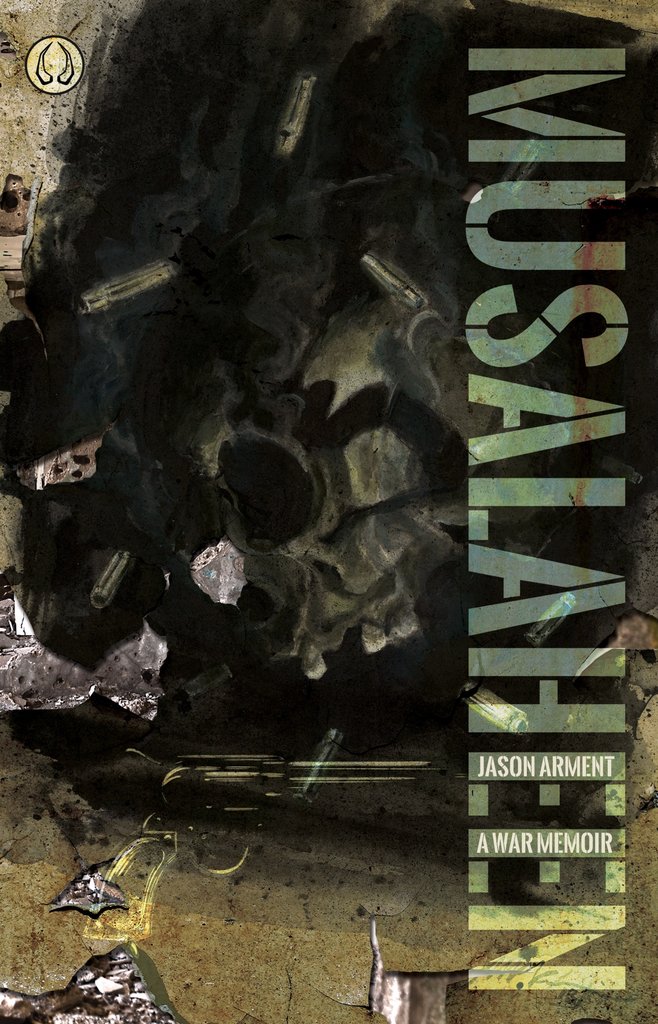

In October I received two books from small presses I love: Musalaheen, from University of Hell Press, and Stranger in the Pen, from Perfect Day Publishing. The first, a war memoir about a Marine in Iraq, I received via an author request for review. I wanted to help Musalaheen’s author, since I’d like to support any Marine who writes creatively, but I have a hard time with art about war. My father is a Navy lifer, a Vietnam and Desert Storm veteran, and I didn’t know if I’d be able to read Musalaheen safely. (I don’t believe in avoiding art experiences due to discomfort. But when your hands shake and your breathing stutters from watching Platoon, better not to watch Platoon.)

A couple of weeks after I received Musalaheen, I got an email from Perfect Day announcing Stranger in the Pen. It’s also a memoir, but it’s about a single day in the life of a Kuwaiti man who was detained overnight at London’s Gatwick Airport in 2017 for literally no reason. How interesting it would be, I thought, to pair the two. I thought they’d offer, if not totally opposing perspectives, certainly different ones. I suspected that I could come up with something wise to say about Western entanglement in the Middle East from these two memoirs.

Well.

The two books were opposites in more ways than I ever imagined. Jason Arment, the author of Musalaheen, was barely of voting age when he entered boot camp. He was a kid from Iowa who’d never known life outside the Midwest. Mohamed Asem, the author of Stranger in the Pen, was an extremely erudite global citizen in his mid-thirties when he was detained at Gatwick. He had lived in several countries and earned a master’s degree. Arment didn’t comprehend his white privilege at the start of the book, while Asem lived with an awareness of his Arabness most of the time he was not in Kuwait. Arment writes without artifice about the physical toll of Marine boot camp and service in Iraq – pants covered in shit, no hot food, weeks of sleep deprivation. Asem requests and receives a gluten-free meal from Gatwick security, and his nervous stomach ejects it. Arment’s book is more than 350 pages, spanning years, while Asem’s is less than 140, spanning about 30 hours.

Musalaheen, Jason Arment. University of Hell Press, September 2018. 402 pp.

Arment’s book slayed me. It is an unforgettable piece of work: dangerously truthful, stunningly rendered, emotionally wide-ranging, relentless. It’s perhaps a little long, because around the 300-page mark, stories and language this hard-hitting start to numb the reader rather than impacting her. But this too is part of the book’s extraordinary effect. For the soldiers there, the Iraq conflict was boring to the point of numbness, with brief periods of terror. Arment’s book is never boring, but it is purposely repetitive, and it communicates the boredom of the war, its haphazard pile of days, its stretched and gooey hours, wonderfully well. It’s a book I’ll recommend for years.

I started right in on Stranger in the Pen after I finished Musalaheen. Asem has a quiet authorial voice, gentle, rhythmic sentences, neat paragraphs, and the ability to thread one subject gracefully through another, like a twining lace pattern. The book includes beautiful writing and a useful schema; its limited space and time does not restrict the range of Asem’s thoughts, and a pleasurable tension results from this juxtaposition. His self-pity is palpable, but he records it rather than excusing it, an admirable narrative choice. And his minute-by-minute experience of improper detainment is compelling.

The reader knows, based on the book’s framing, that Gatwick is going to let him go home in the morning, and that unless he was lying to his family, he’s going home physically unharmed. Unjust detainment is harmful, yes, but it’s not kicking rats out of your path when you head for the latrine in 110-degree heat.

Stranger in the Pen, Mohamed Asem. Perfect Day Publishing, October 2018. 144 pp.

It was quite a shock to go from Arment’s profanity, linear thinking, and self-filleting to Asem’s delicate, geometric assessments of his own character. I had unkind thoughts about Asem. He wouldn’t last one minute on the FOB, I thought. Of course, that is a senseless comparison, based on the two memoirs’ proximity and nothing more. But the whole point of this exercise was to compare the two books, to read them against each other. I had a sinking feeling that either I was doing it wrong, or I was mistaken that it could be done.

By now it was December. I was determined to write about these two books, whose newness to the publishing marketplace was waning by the day. I thought Stranger in the Pen was more accomplished, a Fabergé egg of a book, but Musalaheen was wiser and better. I no longer thought that pairing the two would be politically interesting. Now I just hoped for an angle.

What the books have in common is hardship, but the scope of each is wildly different. Arment’s hardship is animal, based on pushing a human creature to its breaking point through fatigue and obedience. From this, Arment attains wisdom about the wider world, distance from oorah jingoism, and bitter understanding about what brings veterans to their knees. At one point, he fights a dramatic, imaginary war between himself and a soldier he doesn’t recognize in the mess hall:

Asem’s hardship is bureaucratic, mundane, wrapped up in the weirdness of his situation. He’s detained because of his unique status: he has dual citizenship in Kuwait and the United States, but is headed for a flat he owns in London, which he uses as a base for his many travels. It’s odd to the Gatwick passport agents that he owns property in a country in which he has no residency, and that he owns no property in the two countries in which he has residency.

To be sure, that is no reason to hold a person overnight when he is entirely innocent. What was done to Asem is an injustice, certainly one wrapped up with racism and Western xenophobia. But his complex citizenship and his international mobility mean his hardship is not widely representative. In a way, Arment’s isn’t, either, because – although I’ve known a lot of extraordinary soldiers in my life – few men could walk away from his experiences with the acumen he has, with the ability to, for example, break down each moment of a violent encounter with an Iraqi child and rebuild truth out of it. Few men could write so beautifully about the history of a land which bores and frightens and disgusts them:

Comparing the enormity of these two men’s hardships is unnecessary. There is no sweepstakes for suffering. Comparing the shape and form of their hardships, though clinically intriguing, leads largely to despair. Things are bad all over, from Gatwick to Fallujah, and horror stalks humans in all contexts, whether via a self-important passport officer or an IED turning your bunkmate into Jell-O.

What is left in the wreckage of Musalaheen and Stranger in the Pen? Insight, for one thing. Intelligence so discerning that it illuminates everything it touches. A reminder that negative capability is the only way to live, and that recognizing our common humanity will save the day more meaningfully than an M-16 or a locked door will. After he returns from Iraq, Arment fights everybody, for no reason; it takes him years to make sense of his service. The long-term effects of Asem’s detainment are not covered in his book; the banality-of-evil quality of his injustice is the main takeaway.

Despite my hypothesis, neither book issues a statement on the collision of the post-9/11 West with the Middle East. Both of them rely on this context, but the stories of these two men are too personal, too humanist at their core, to perform political analysis. They are still remarkably valuable artifacts from this rotten time in world politics. Despite oppressive systems, good men must write their truths.

header image: “kuwait airways boeing 777-369 9K-AOH,” paul evans / flickr