American, Gothic: Victor LaValle’s Destroyer

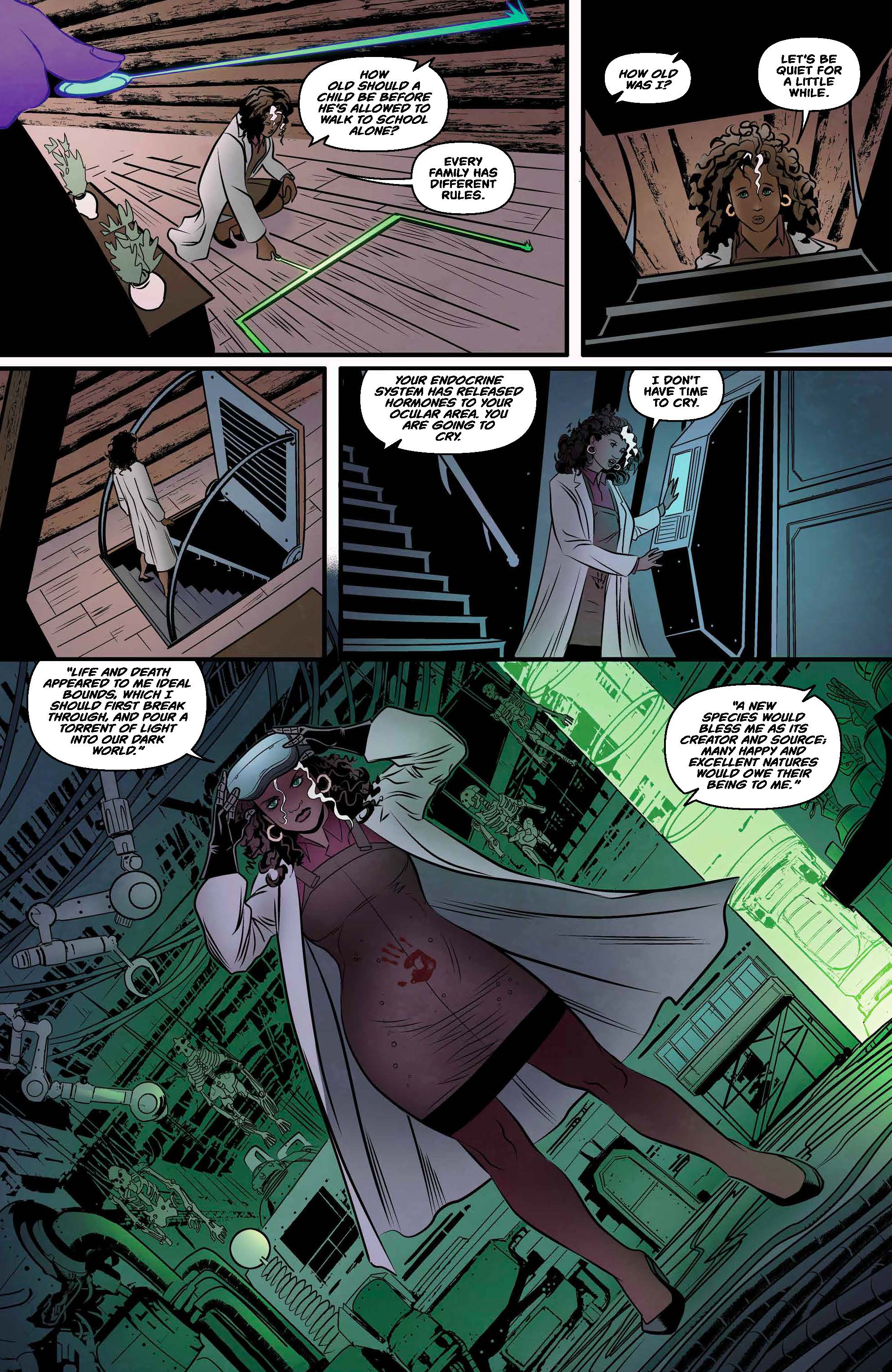

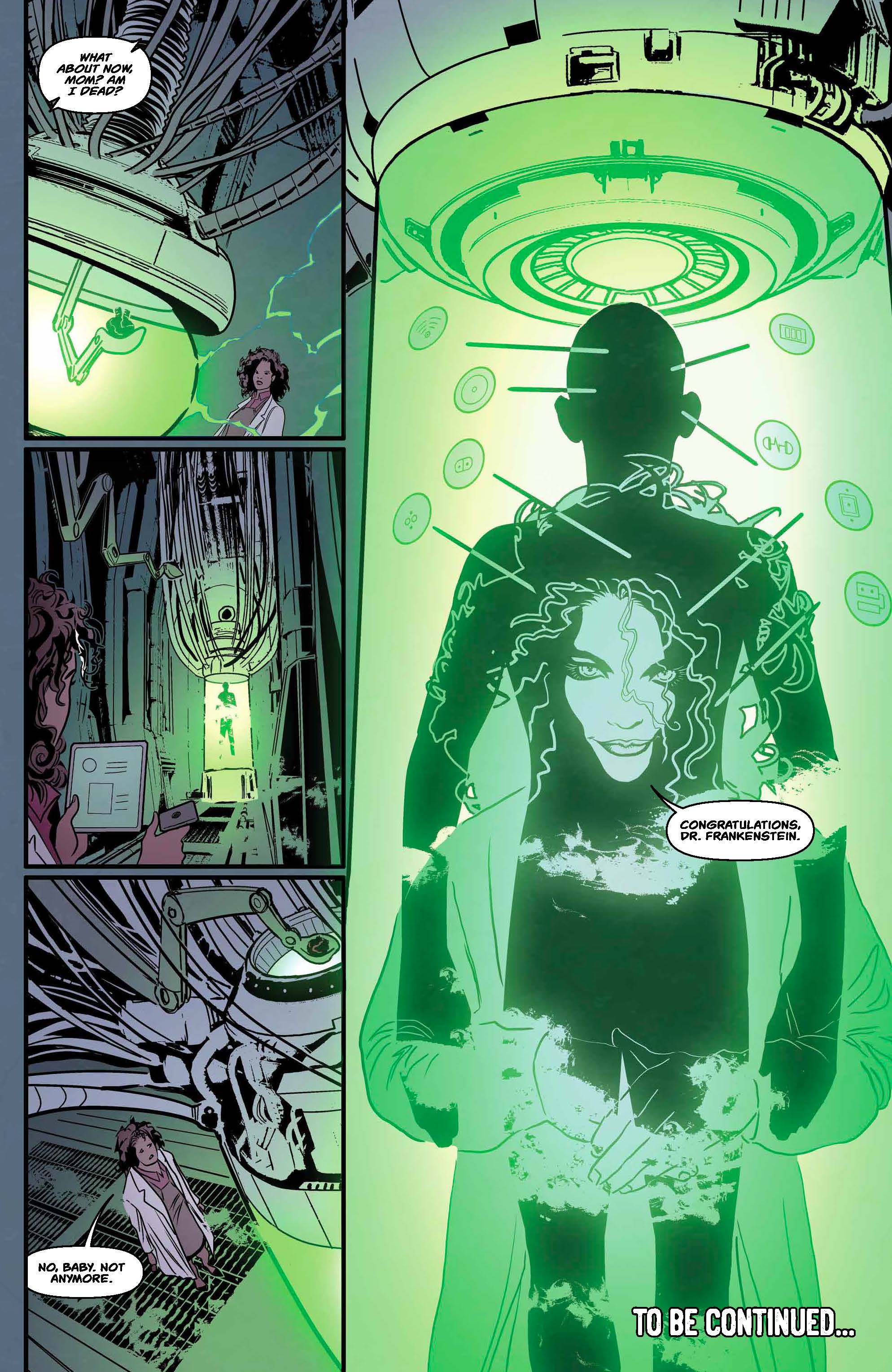

Victor LaValle’s comic book series, Destroyer, fits the impossible over our everyday American nightmare. In it, Dr. Josephine Baker, a brilliant scientist and descendant of Victor Frankenstein, uses nanobot technology to reanimate her 12-year-old son after he is killed by police in a shooting that mirrors the very real death of Tamir Rice. Her former employer, a company called The Lab, wants to repossess the technology that allowed her to bring her son back from beyond the veil of death, at any cost. Oh, and Dr. Frankenstein’s Creation, dormant for centuries in Antarctica, is now rampaging across the globe. This is a beautifully illustrated story of how grief and rage are twins born in the same miscalculations, and a surprisingly prescient allegory for exorcising America’s oldest demon.

I spoke with LaValle in September for sinkhole. Here is our conversation.

When I read this series, and in fact, when I read the news, I see an ongoing conversation between white fear and black/brown grief. To what extent are fear and grief animating your story? Is it fair to say those are also the animating forces in our culture today?

I'd say one of the great American themes is fear. Not so surprising when one considers the history of this wild experiment we're all involved with. There's an idea that always irks me in the rhetoric of the Puritans – those early European immigrants – they often speak of the belief that the untamed expanses of what will become the United States are filled with devils and monsters. It becomes a bedrock belief of these early settlers that their job is to spread the gospel of Christianity, in part, to cleanse or purify the country they've reached. Many horror movies –The Witch is a recent example – make a great deal of the idea that there's evil out in those woods. But I would submit that those Puritans brought as much evil as they found. But it would require too much introspection to see the world that way. So instead they read evil into the territories and found a justification for their fear of it. That fear was planted early in the narrative of the European in the Americas. It has yet to be pruned. When that fear is allowed to grow unchecked it too often turns to violence and, more often than not, it's black or brown or (originally) red people who are the brunt of that violence. It's fair to say those forces animate our culture today only because they have always been a part of the culture of the United States.

In your scripts for this series, to what extent do you specify visual flourishes that end up in finished issues – how the nanobots work, or the hand print on Dr. Baker's apron, for example?

I certainly include details I'd like to see on the page, that hand print for instance or the little rubber ducky in a childhood photo of Akai (if you look closely it's a Frankenstein rubber ducky toy). I love planting that stuff and the artist, Dietrich Smith, makes the images come to life beautifully. There are plenty of things I couldn't describe, or imagine, the first image of the Monster in issue #1 for instance. My script said, The Monster sits on an iceberg. It's the enduring brilliance of Dietrich's talent that created an image as glorious as that one. He pulls off that kind of thing a dozen times per issue. The man is good.

What kind of reading/art did you take in while you were breaking the series, and how do you think it's affected the story so far?

I didn't study too much in order to write the scripts, not in the immediate sense. Instead I'd been thinking about the series for almost two years before I pitched it to BOOM Studios. So I had a great deal of it in mind long before I got to the actual writing. That said, the two editors – Eric Harburn and Chris Rosa – were true collaborators, regularly pushing me to think with greater visual flourish if I ever wrote scenes that felt sluggish or bland.

I'm really fascinated by the Creation, whom we first see diving off an ice float into Arctic waters. I can tell that he has some kind of moral sense, and an impulse to protect innocence, but the violence he ends up inflicting on his surroundings still ends up being kind of indiscriminate. Would it be a big spoiler for you to give your thoughts on why he operates that way?

The Creation is called the Monster throughout the comic and that's on purpose. In Mary Shelley's original novel he was a Creation but a few hundred years have hardened him, changed him; by the time of our story he really is a being of rage, a Monster. In the opening the Monster shows a great deal of affection for the whales he swims with, but he equates innocence with the non-human world solely. As far as he's concerned there are no innocent humans. And if you imagine the world from his point of view I would say he's got a damn good case. Many of us are trained to think of innocence or goodness as an individual trait. If I act nicely toward others, if I mean well, then I am good, I am innocent. I call bullshit on that. The Monster sees us as a species of murderers, a species who – through our very existence – endangers all other life. Where is the lie? It might seem kind of grim, but I think he's actually ruthlessly logical. Doesn't matter if you're a whaler or an anti-whaler, a woman or a child. If you are human, you are his enemy.

I'm not a parent yet and I'm already anticipating having the police conversations with my future kids. But one of the things Destroyer does is let me indulge in a fantasy of being able to send my kids out into the world with less fear for their lives. Is it foolish to see your series as a kind of lullaby for parents like Dr. Baker – parents of black and brown children?

Well, if I could rebuild my kids with nanobot technology I'd certainly do it just to keep them both safe. I'd say there's a sadder idea at the heart of this series. It's my fear, as the parent of a black son and daughter, that the only way I could ever be sure my children were truly safe would be if I could turn them into androids. Imagine a world so antagonistic that I even have to consider such a thing.

In the endnote to Issue 3, you write that it's the responsibility of a just society to truly see all of its Creations. Can you elaborate a bit on what Creations you'd like America to acknowledge?

Of course by that I mean that every child born in this country (and in any country) should actually be born into the birthrights of all its citizens. The idea that your society, your government, your education system, your law enforcement, your banks and businesses actually wanted to support the growth and safety of every human being living within its borders, it's insane that such a thing should even be considered a radical idea. The history of the United States (and many other countries too) is that clearly we are far off from a just society like this. But that doesn't mean it can't be reached. It will just mean remained awake, aware, and active. Here's to that age old fight.

header image: victor lavalle / photo credit: teddy wolff

Victor LaValle is the author of the short story collection Slapboxing with Jesus, four novels, The Ecstatic, Big Machine, The Devil in Silver, and The Changeling and two novellas, Lucretia and the Kroons and The Ballad of Black Tom. He is also the creator and writer of a comic book Victor LaValle's DESTROYER, published by BOOM! Studios.

He was raised in Queens, New York. He now lives in Washington Heights with his wife and kids. He teaches at Columbia University.